Managing Technical Debt

Introduction

The concept of technical debt is a metaphor that describes the trade-off between the short-term benefits of rapid development and the long-term costs of maintaining a codebase. Just as financial debt can be used to finance immediate needs, technical debt can be used to deliver features quickly. However, like financial debt, technical debt must be repaid with interest. If left unaddressed, technical debt can accumulate and slow down development, increase the risk of bugs, and make it harder to add new features.

The phrase was originally coined by Ward Cunningham in order to explain to non-technical stakeholders why resources needed to be budgeted for refactoring work. Think of it as a loan that you take out to get a feature out the door faster. You still have to pay it back, but you can choose when and how to do so.

Most developers have a much lower opinion of technical debt than other stakeholders. This is because developers are the ones who have to deal with the consequences of technical debt. However, technical debt is not always bad. Just as financial debt can be used to finance a house or a car without needing to save up for a long period of time, technical debt can be used to deliver features quickly. The key is to be aware of the trade-offs and to manage technical debt effectively.

Different Definitions of Technical Debt

There are many different definitions of technical debt, and the term is often used in different ways by different people. Some people use it to refer to any code that is not up to their standards, while others use it to refer to code that is causing problems in production.

Definition 1

Robert Martin, author of Clean Code, takes a somewhat narrow view of technical debt.

"A mess is not a technical debt. A mess is just a mess.Technical debt decisions are made based on real project constraints. The decision to make a mess is never rational. It's always based on laziness and unprofessionalism and has no chance of paying off in the future.”

-- Robert Martin

By this definition, technical debt is always a conscious decision to take a shortcut in order to meet a deadline. It is a deliberate choice to incur a cost in the future in order to deliver a feature quickly. Restricting it to only conscious decisions makes some sense, but contradicts how much of the industry uses the term. It doesn't allow for the idea that technical debt can be incurred accidentally, developers make mistakes, and viewing the correcting of those mistakes as paying down technical debt is a useful metaphor.

Definition 2

Steve McConnell, author of Code Complete, has a broader definition of technical debt. He divides it into two categories: intentional and unintentional.

- Intentional technical debt is incurred when a developer makes a conscious decision to take a shortcut in order to meet a deadline. This is similar to Robert Martin's definition.

- Unintentional technical debt is incurred when a developer makes a mistake that they are not aware of. This could be due to a lack of experience, a lack of knowledge, or a lack of understanding of the codebase.

This definition is much closer to how the industry as a whole tends to define technical debt. It allows for developers to make mistakes and treats technical debt as a more natural part of the development process.

Definition 3

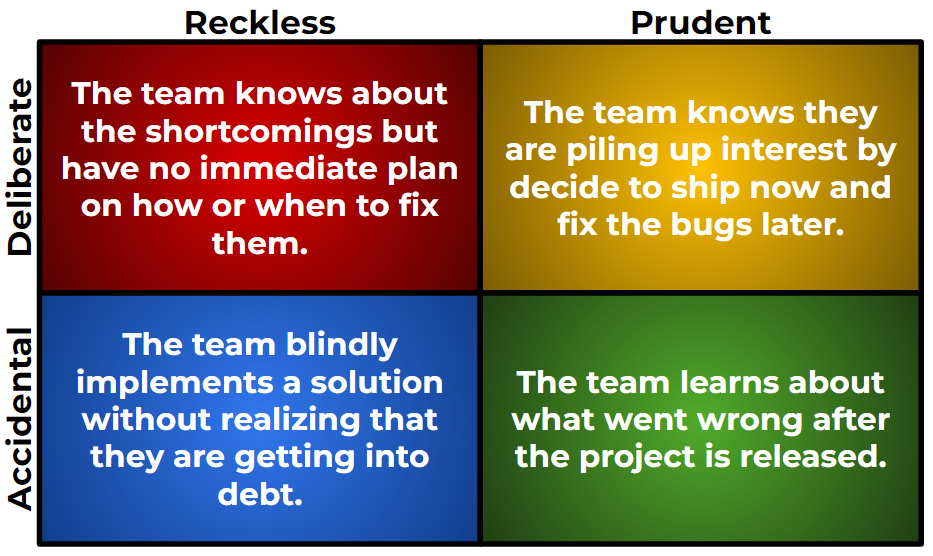

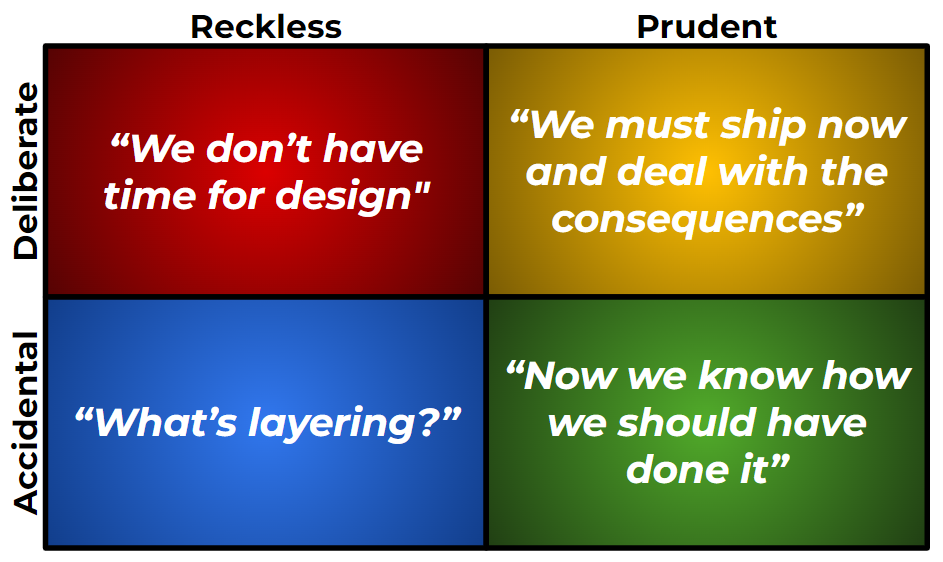

Martin Fowler, author of Refactoring, has an even more nuanced view of technical debt. He classifies technical debt as being either deliberate or inadvertent, depending on whether it was incurred intentionally or not. He also distinguishes between two types of technical debt: reckless and prudent, depending on whether it was incurred with full knowledge of the consequences.

That gives us four quadrants of technical debt:

Some possible examples of each quadrant are:

Definition 4

A fourth definition of technical debt comes from a 2014 paper published by the Software Engineering Institute. They divide tech debt into 13 distinct types, with a set of key indicators for each type.

- Architecture Debt

- Build Debt

- Code Debt

- Defect Debt

- Design Debt

- Documentation Debt

- Infrastructure Debt

- People Debt

- Process Debt

- Requirement Debt

- Service Debt

- Test Automation Debt

- Test Debt

This is a much more detailed and comprehensive view of technical debt, but it can be difficult to apply in practice. I prefer to stick with the technical debt quadrants as a more practical way of thinking about technical debt.

Causes of Technical Debt

If we use Martin Fowler definition of technical debt, we can see that there are many different ways that technical debt can be incurred. Some of the most common causes of technical debt include:

- Financial or Staffing Constraints: When cost is the primary motivator for a technical decision, technical debt usually follows. Tech debt allows progress at a reduced code in the short term, but it will eventually cause problems.

- Tight Deadlines: Rushed or unreasonable deadlines require developers to take shortcuts in order to deliver on time. Of all the causes of technical debt, this is probably the most common.

- Unclear Requirements: Major requirements changes mid project often result in the system design being a bad fit. The initial architecture might have been ideal for the original requirements but often has issues with the updated ones.

- Lack of Experience: Junior developer often lack the experience to understand the impact their design decisions will have in the long term. Input from senior engineering is critical for avoiding tech debt.

- Outsourcing Critical Decisions: When critical decisions are made by non-technical stakeholders, they often don't understand the technical implications of their decisions. The DevOps reports have shown that if developers have a sense of ownership over the code, they are more likely to produce higher quality code.

- Top-Down Management: When management dictates technical decisions, developers are often forced to implement solutions that they know are not ideal. This can lead to resentment and a lack of motivation to produce high-quality code. Once again, a sense of ownership over the code can help to mitigate this.

Numerous online companies took on significant technical debt during the Covid-19 pandemic. The sudden shift to remote work and a massive increase in online shopping caused many companies to take shortcuts in order to keep up with demand. This led to a significant increase in technical debt, with consequences that were often all too apparent. Security breaches, outages, and data leaks have all been linked to technical debt incurred during the pandemic.

Remember that the early estimates of the pandemic were that it would last a few weeks. Companies that took on technical debt in order to meet the initial demand were often caught off guard when the pandemic restrictions lasted much longer than expected.

Consequences of Technical Debt

Technical debt itself is not good or bad. It's a tool that can be used to meet deadlines or to save money in the short term. The problem is when technical debt is not managed properly. If you are not aware of the trade-offs that you are making, then you are setting yourself up for failure.

The biggest issue is when technical debt is allowed to accumulate without being managed. It can start to have significant consequences for the project and the company. The codebase will become harder to work on, and the cost of making changes will increase. The system will become more fragile and more bugs will be introduced with each change. Eventually this leads to reduced team momentum. If not addressed it will eventually lead to morale problems and developers leaving the team.

Not all technical debt is created equal. If the issue is isolated to a rarely modified portion of the codebase, then the consequences will be minimal. However, if the technical debt is in a critical part of the codebase, then the consequences can be severe.

Some of the most common consequences of technical debt include:

- Reduced Velocity: As the codebase becomes harder to work on, the team's velocity will decrease. This can lead to missed deadlines and unhappy stakeholders. The team will have to spend time refactoring the code to fix the quick-fixes implement previously, just to get the code in a state where new features aren't as painful to add.

- Poor Design: A messy code base tends to lead to messy changes in the future. If developers get into the habit of taking shortcuts, you'll see the overall structure start to deteriorate with time.

- Performance Issues: Building a performant system requires careful planning and control over how the pieces interact. A hacked together solution will often have performance bottlenecks that won't be apparent until the system is deployed at scale.

- Security Vulnerabilities: Security is often an afterthought when technical debt is incurred. Quick fixes are much more likely to have weaknesses that can be exploited by an adversary to gain access they shouldn't have.

- Testing Strain: Test coverage is often the first thing to go when technical debt is incurred. QE teams end up overworked and under-resourced, leading to missed bugs and a general lack of confidence in the system.

- Morale Issues: Developers want to work on high-quality code. If they are forced to work on a messy codebase, they will become demoralized and less productive. This can lead to a downward spiral where the codebase becomes even messier and the team's velocity decreases even further.

Managing Technical Debt

Every codebase will have some tech debt, and every company will choose to manage it in their own way. Some choose to dedicate all of their engineering time to building new features and never address their tech debt at all. That approach will inevitably fail, causing system failure and production delays.

Identifying Technical Debt

Assuming that your company is actively trying to manage technical debt, the first step is to identify it. This tends to be rather subjective, and probably should be subjective. Developers are the ones who have to work with the code, so they are in the best position to identify the most important technical debt. If a piece of code is causing developers to slow down, is causing bugs, or even just a source of irritation, then it is probably technical debt and needs to be tracked.

Creating a tech debt backlog is a good way to track the technical debt in your codebase. This can be as simple as a list of issues in your issue tracker, or as complex as a dedicated tech debt tracking system. The key is to make sure that the tech debt is visible and that it isn't being hidden or ignored.

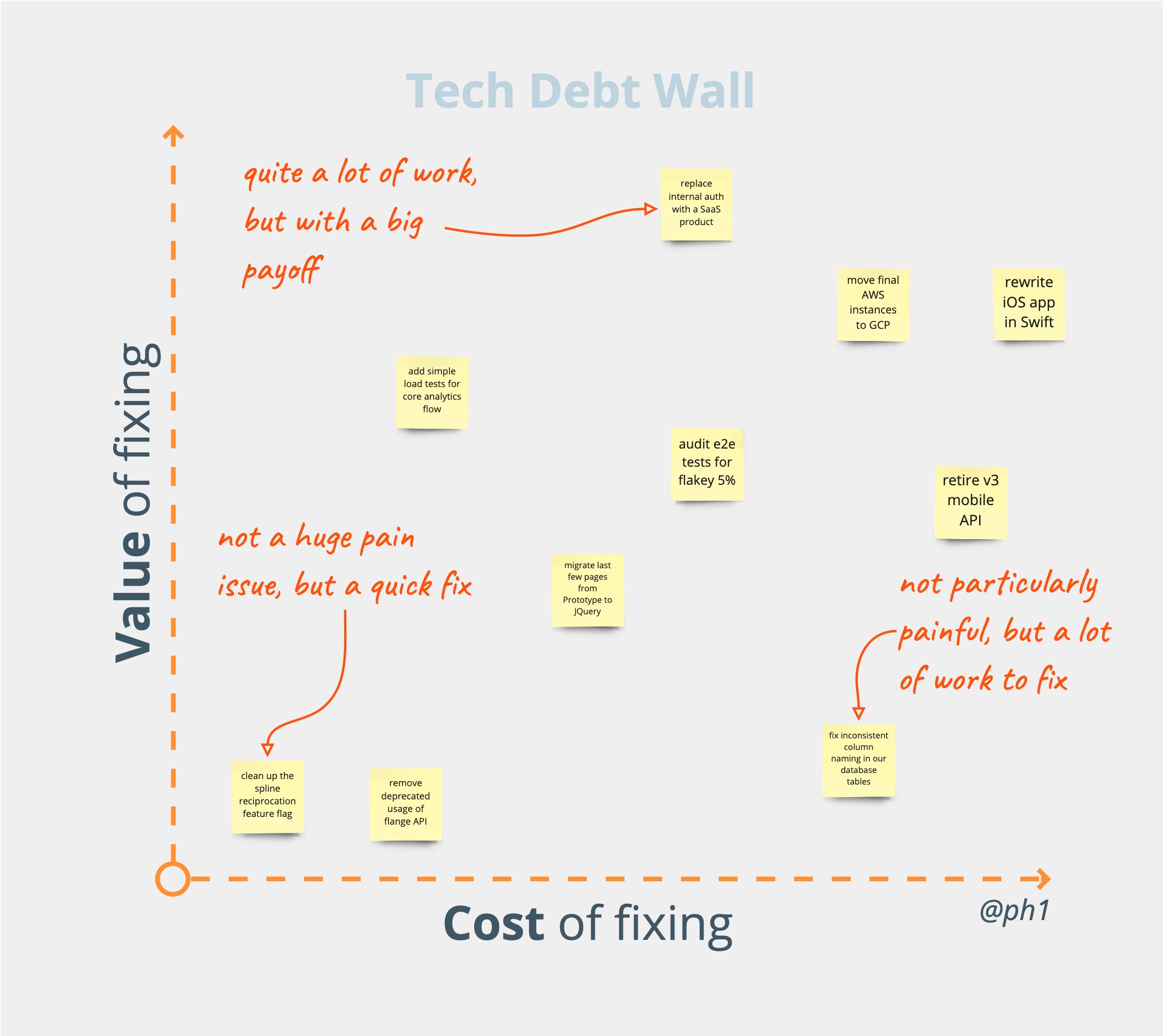

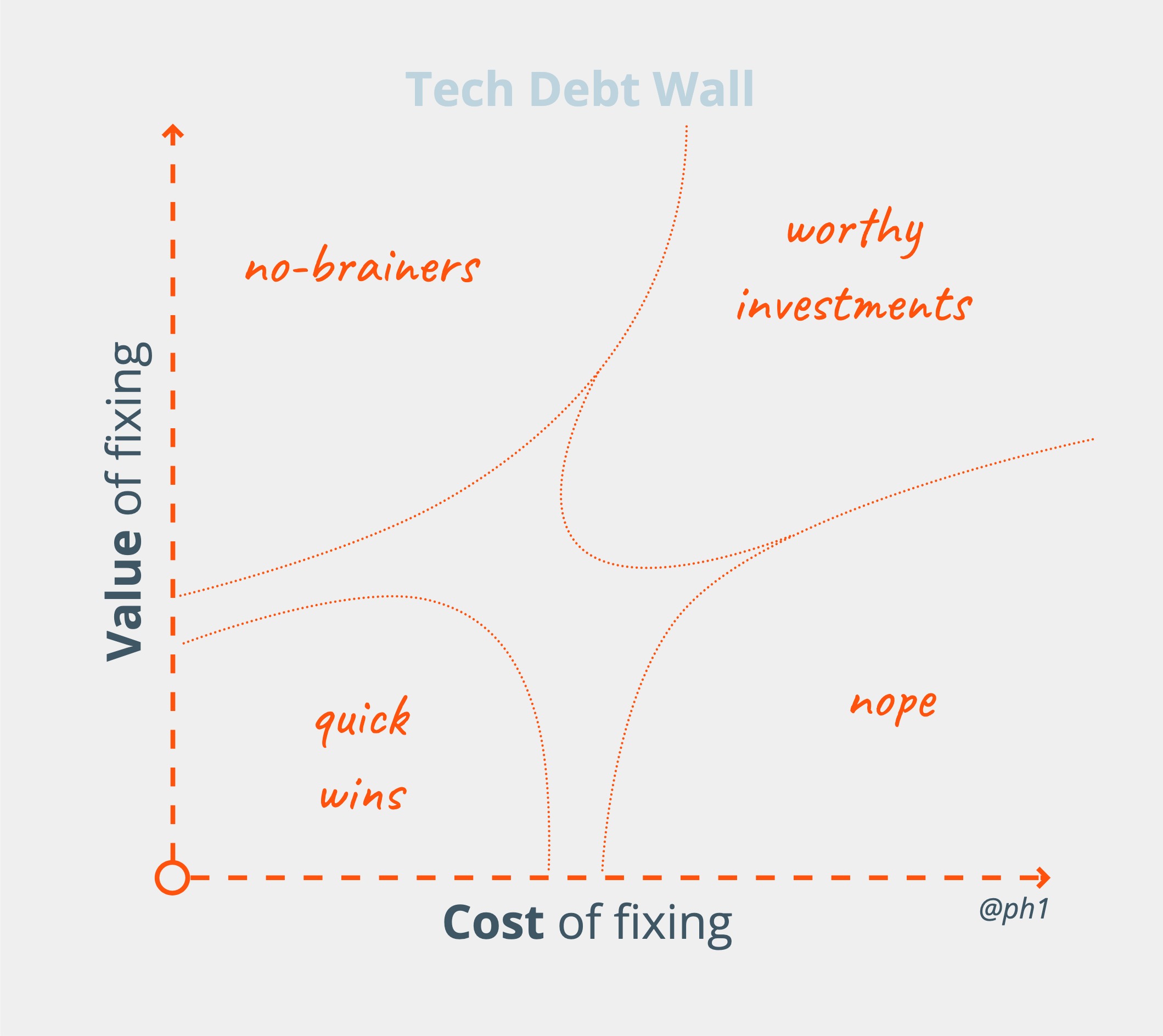

Tech Debt Wall

A simple backlog with estimates is rarely enough to clearly communicate the amount and importance of any debt the team has. Just knowing the time it would take to fix a piece of debt doesn't say anything about the value of fixing it. The value gained by fixing a piece of technical debt is often proportional to the amount of time that developers spend working in that part of the codebase. If a piece of code is rarely touched, then the value of fixing it is low no matter how easy it is to fix. If a piece of code is touched frequently, then the value of fixing it is high, and even if the fix is difficult, it is probably worth it.

My preferred approach for tracking technical debt is to use a tech debt wall, which is an approach publicized by Pete Hodgson. The images below are taken from his blog post.

The tech debt wall is a physical or virtual wall that tracks each piece of tech debt by its value and its cost to fix. The value is determined by how irritating the tech debt is to developers, and the cost is determined by how difficult it is to fix. This allows the team to prioritize the tech debt that will provide the most value for the least cost.

For example:

We can think about the tech debt wall in terms of regions.

- Quick Wins: Anything in the bottom left corner is a quick win. These are pieces of tech debt that are easy to fix but don't provide a lot of value. They should be dealt with whenever there is a lull in the development process.

- No Brainer: Anything in the top left corner is a no-brainer. These are pieces of tech debt that are easy to fix and provide a lot of value. They should be tackled as soon as they are identified.

- Worthy Investments: Anything in the top right corner is a worthy investment. These are pieces of tech debt that are difficult to fix but provide a lot of value. Their complexity probably means that we'll need to work with stakeholders to get time allocated to fix them.

- Nope: Anything in the bottom right corner isn't worth fixing. These are pieces of tech debt that are difficult to fix and don't provide a lot of value. Sometimes this is because the code is rarely touched, or perhaps is just easy to work around. Unless something changes to make these pieces of tech debt more valuable or easier, they should be left alone.

Note that items can move around the wall as the team works on the system. An issue in a rarely touched area of the codebase might suddenly jump in value if a new feature requires a lot of work in that area.

Paying Down Technical Debt

Once you have identified the technical debt in your codebase, the next step is to pay it down. This can be a difficult process, as it often requires taking time away from building new features. There are several strategies for allocating development time to pay down technical debt.

- As part of other work: The most common strategy is to just assume developers will fix technical debt as part of their regular work. This is the least effective strategy, as most developers will prioritize building new features over fixing technical debt. This approach can sometimes deal with small pieces of technical debt, but it is unlikely to deal with larger issues.

- Dedicated time: A more effective strategy is to allocate a certain amount of time each sprint to fixing technical debt. This ensure that technical debt is being regularly addressed, and that it is not being ignored in favor of building new features. It treats tech debt the same as any other work item, but it can be difficult to get buy-in from stakeholders. It also struggles to handle large pieces of tech debt, as they often require more time than can be allocated in a single sprint.

- Tech debt sprints: A more radical approach is to dedicate an entire sprint to fixing technical debt. This can be an effective way to deal with large pieces of technical debt, and allows for a more focused approach to fixing tech debt. However, it can be difficult to get buy-in from stakeholders, as it means that no new features will be delivered during the sprint.

Note that teams might need to switch between these strategies depending on the amount of technical debt in the codebase. If there is a large amount of technical debt, then a dedicated sprint might be the best approach. If there is only a small amount of technical debt, then fixing it as part of regular work might be sufficient.

When Should You Take on Technical Debt?

Sometimes a shortcut is the right path. While I usually concentrate on crafting the best design I can, there are times when I just need to get the code finished. There are three main cases where I will take on technical debt.

Prototyping or POCs

If I'm building a prototype or a proof of concept, then my only goal is to finish as quickly as possible. I'm not concerned with maintainability or extensibility. I just want to show that the idea works. The purpose of a prototype is to learn, not to build a production system. Once I've covered what I need to learn, I'll throw the prototype away and start over with a clean slate. You should rarely be building on top of a prototype, the consequences of doing so are often disastrous.

Emergency Fixes

Sometime critical stuff breaks and you need to fix it quickly. If the system is down or if the bug is causing data loss, then you need to fix it as quickly as possible. You don't have time to consider the long-term consequences of the fix. You just need to get the system back up and running. Once the system is stable, you can go back and clean up the fix.

Exploration

Sometimes you need to explore a new technology or a new approach. You don't know if the technology is going to work, so you don't want to spend a lot of time building a perfect solution. You just want to build something quickly to see if it works. If it does work, then you can go back and build a better solution. If it doesn't work, then you can throw it away and start over.

Racing to Market

The final case is when you are racing to market. If you are in a competitive market and you need to get a feature out the door quickly, then you might need to take on technical debt. The key is to be aware of the trade-offs that you are making and to have a plan for paying down the technical debt in the future.

Conclusion

Technical debt is often seen as a necessary evil in software development. It allows us to deliver features quickly, but it comes with a cost. If not managed properly, technical debt can accumulate and slow down development. The key is to be aware of the trade-offs that you are making and to manage technical debt effectively. By identifying technical debt, paying it down, and knowing when to take on technical debt, you can balance codebase health with business needs more effectively.