Code Reviews

Introduction

Code reviews are the process of sharing code changes with your team members and getting feedback before merging them into the main codebase. It gives your team members a chance to offer feedback, catch bugs, and suggest improvements. They have become a required practice in most software organizations because they have been shown to improve code quality, reduce bugs, and help team members learn from each other.

Teams that do code reviews well produce higher quality code, have fewer bugs, and are more productive. They also have a shared understanding of the codebase and the system architecture, ensuring that everyone can work on any part of the codebase.

If done poorly, code reviews can be a source of conflict and frustration. They can slow down development, create bottlenecks, and lead to resentment among team members. To avoid these problems, it's important to establish clear guidelines and expectations for code reviews and to make sure that everyone on the team understands and follows them.

Overview

Types of Code Reviews

There are several different types of code reviews, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The most common types are:

- Formal Code Reviews: This is typically a scheduled meeting of 3-6 developers and testers who review the code together. The author of the code presents the code, and the reviewers ask questions, make suggestions, and provide feedback. This type of code review is time-consuming and can be intimidating for some team members, but it can also be very effective at improving the overall design of the code.

- Informal Code Reviews: This is the most common form of code review. It is a less structured review that is usually done as part of a pull request or code commit. The author of the code sends the code to one or more team members for review, and they provide feedback via comments or in person. This type of code review is less time-consuming than a formal code review and can be done asynchronously, but it may not be as effective. It's quality is highly dependent on the reviewer.

- Pair Programming: In pair programming, two developers work together on the same code at the same time. This can be an effective way to catch bugs early and share knowledge, but it can also be time-consuming and require a high level of coordination between team members. It can be a good way to onboard new developers or to work on complex features where the design is uncertain.

- Tool-Assisted Code Reviews: Modern AI tools are starting to be used to assist with code reviews. These tools can automatically analyze code changes, identify potential bugs, and suggest improvements. They can be a useful complement to human code reviews, but they are not a substitute for human judgment. If you rely too heavily on these tools, you miss out on the learning opportunities that come from human code reviews.

Objectives

All code reviews have the same basic goal. They are intended to make sure that the overall health and quality of the codebase is maintained or improves over time. There are also many other benefits to code reviews, including:

- Teaching and mentoring newer developers

- Preventing bugs and security vulnerabilities

- Improving code readability and maintainability

- Familiarizing team members with the codebase

General Guidelines

Code review are more effective if you follow some general guidelines:

- Limit the size: Smaller code changes are easier to review and are less likely to introduce bugs. Limiting changes to 200-400 lines of code is a good rule of thumb. If a change is larger than that, then you should try to break it into smaller pieces that can be reviewed independently.

- Don't spend more than an hour: Code reviews should be quick and focused. Spending too much time on a code review can lead to diminishing returns. Longer reviews have been shown to have a lower bug detection rate. This goes hand in hand with limiting the size of the change.

- Self-review first: Before sending your code to a team member for review, review it yourself. This can help you catch simple bugs and will make the review process faster and more efficient.

- Abandon perfectionism: Code reviews are not about finding every bug or suggesting every possible improvement. They are about improving the overall quality of the codebase. Don't get bogged down in minor details. When you approve a change, you aren't saying that it is perfect, you are saying that it is good enough to move forward.

Common Mistakes

Not every developer likes or appreciates the code review process. Their complaints usually stem from one of the following common issues:

- Timely feedback: If you end up waiting for feedback for days, then the reviews are a barrier to progress.

- Lack of context: If the reviewer doesn't understand the context of the code, then the feedback is likely to be less useful.

- Improper tone: If the feedback is delivered in a harsh or condescending tone, then the author is less likely to be receptive to it.

- Ego: If the reviewer is more focused on showing off their knowledge than helping the author, then the feedback is likely to be less useful. This issue can also manifest in the author being defensive about their code.

Fixing any of these issues requires a commitment from the entire team. It's important to establish clear guidelines and expectations for code reviews and to make sure that everyone on the team understands and follows them. Whether developers like code reviews or not, they are a necessary part of the software development process, and have been shown to improve code quality and reduce bugs.

Code reviews are only as effective as the worst reviewer on the team. If one team member is only ever doing the Terms of Service review, where they just scroll to the bottom and click "Approve", then the code review process is not going to be effective. Other developers on the team will quickly realize that they can get away with sloppy code, and the overall quality of the codebase will suffer.

Don't be that person, and don't rely on that person. Learning to value feedback on your code, especially when it's critical, is an important part of becoming a better developer.

Reviewing Code

What to Look For

When reviewing code, you will never be able to completely understand the author's intent. Doing so would require as much time as it took to write the code in the first place. Instead, you need to narrow your focus to the most important aspects of the code.

If you are a new developer, or just unfamiliar with the codebase, then your main objective should be to learn more about the system. Use the review as an opportunity to ask questions and get clarification on parts of the code that you don't understand. You are unlikely to be able to catch bugs or suggest improvements, but that's okay. Your main goal is to learn.

If you are more experienced, then your main objective should be to identify issues or omissions. You should be checking to see if the new code fits well with the existing architecture, if it is well-documented, and if it is easy to read and maintain. Do you know of better ways to implement the feature? Are there any edge cases that the author hasn't considered? These are the types of questions you should be asking.

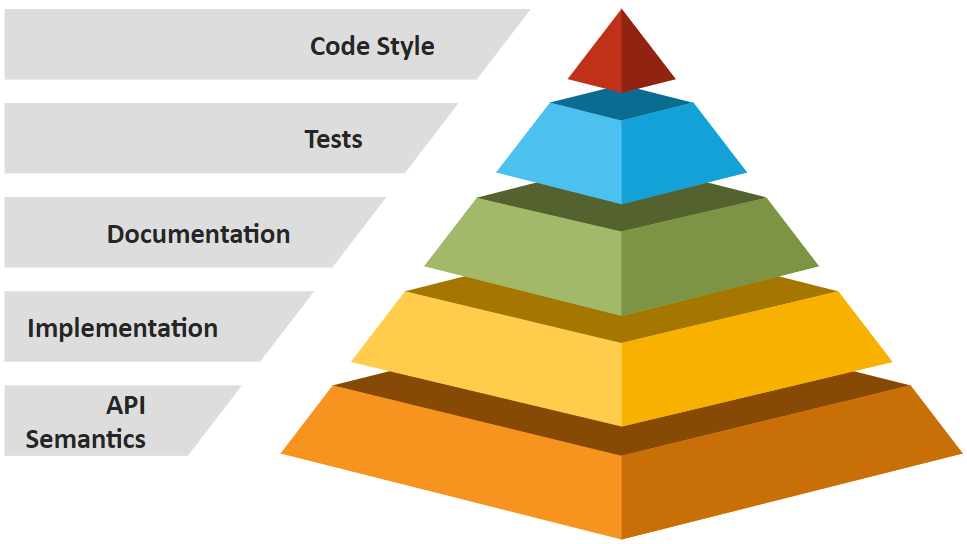

Code Review Pyramid

It's impossible to review everything, so you need to prioritize the most important aspects of the code and focus on that. My preferred approach is to use the Code Review Pyramid, which comes from this excellent blog post by Gunnar Morling. He, quite reasonably, points out that a disproportionate amount of time is spent reviewing things that could be automated and on the most critical aspects of the code.

The core idea behind the Code Review Pyramid is that you should spend most of your time reviewing the base of the pyramid, which is the most important and can't be checked through automation. Items at the base of the pyramid are more important and much harder to fix later on. The higher you go up the pyramid, the easier they are to change later.

Gunnar Morling primarily works on OpenSource projects that are exposed through APIs, so his pyramid is biased towards that. You may need to adjust the pyramid to fit your own project. For example, if you are working on a project that has a lot of UI components, then you may want to add a layer for UI/UX.

Regardless of the type of project, the core idea remains the same. Focus on the things that are most important and hardest to change later on.

API Semantics

The base of the pyramid is API semantics. This refers to the externally facing API of the system. It's the most important part of the codebase because it's the part that is most difficult to change later on. If you get the API wrong, then you will have to live with that mistake for a long time because changing it will break all of the clients that depend on it.

Consider questions like:

- Is the API sized correctly? Does it provide everything it needs to without including anything extra?

- Is there just one way of doing something, and not multiple ways?

- Is it consistent, does it follow the principle of least surprise?

- Is there a clean split between the API and internals without the internals leaking in the API?

- Are there no breaking changes to the user-facing parts of the API?

- Is the API generally useful and not overly specific?

If your project doesn't have an external API, you can think of this as the public interface of the class or module you are reviewing.

Implementation

The next layer of the pyramid is the implementation details. This is the actual logic written in the code. It's important to get this right, but it's easier to change than the API. If you get the implementation wrong, you can always refactor it later on.

Consider questions like:

- Does the change satisfy the original requirements?

- Is it logically correct?

- Does it avoid unnecessary complexity?

- Is it robust? No concurrency issues, proper error handling, etc

- Is it performant?

- Is it secure? Not vulnerable to SQL injection or other types of attacks.

- It is observable? Are things being logged appropriately? Are metrics being reported? Does it have tracing if expected?

- Are there newly added dependencies that are incompatible with your license or that aren't doing enough to justify their inclusion?

Documentation

The third layer of Gunnar's pyramid is documentation. Because he works on OpenSource projects, this is more important for him than it might be for you. Documentation in OpenSource project is something that gets exposed to all system users. In a closed-source project, you might not need to worry about this as much.

Consider questions like:

- Are any new features reasonably documented?

- Are all relevant kinds of docs covered? README, API docs, user guides, reference docs, etc?

- Are the docs understandable with there no significant typos and grammar mistakes?

- Are the docs up-to-date with the code?

This layer is one that many developers disagree with. They feel that documentation is a waste of time and that the code should be self-documenting. While I agree that self-documenting code is the best kind of code, I also know that it's not always possible. Sometimes you need to explain why you did something in a certain way, or you need to explain how to use a feature. In those cases, documentation is necessary.

Having understandable documentation is not something that can be automated. It requires a human to read it and make sure that it makes sense. That's why it's placed here in the pyramid.

Tests

High quality code is supported by high quality tests. Having them as part of a feature demonstrates to the team that the author has thought about how the feature should work and has taken steps to ensure that it works as expected.

Consider questions like:

- Are all tests passing?

- Are new features reasonably tested?

- Are mocks and other testing techniques being applied correctly?

- Are corner cases tested?

- Is it using unit tests where possible and integration tests where necessary?

- Are there tests for non-functional requirements, e.g. performance?

Tests can tell you a lot about the code and the health of the codebase, but most checks can be automated.

Code Style

Most coding style issues can be caught by automated tools. They are the least important part of the code review process, but they are still important. Consistent code style makes the codebase easier to read and maintain. It also helps new developers get up to speed more quickly.

Consider questions like:

- Is the project’s formatting style applied?

- Does it adhere to the agreed on naming conventions?

- Is it DRY?

- Is the code sufficiently readable (method lengths etc)?

If your only feedback on a code review is about code style, then you might be missing opportunities to add automated checks to your build pipeline.

Static Analysis

Static analysis tools can help you catch many of the issues that are at the top of the pyramid. They can help you catch code style issues, potential bugs, and security vulnerabilities. There are a wide variety of static analysis tools available, and if your organization doesn't already use one, then you should consider adding one to your workflow.

Since I am primarily a Java and Kotlin developer, I am most familiar with the tools available for those languages. My typical build pipeline includes PMD and FindBugs for static analysis. PMD is a code analyzer that finds common programming flaws like unused variables, empty catch blocks, unnecessary object creation, and so forth. FindBugs is a program that uses static analysis to look for bugs in Java code. I mostly use it to find potential security vulnerabilities.

There are similar tools for most languages, so you should look for ones that fit your needs.

When using this sort of static code analysis tool, it is important not to ignore any warnings that you might see. The same is true for IDE warnings. When a project goes from 2000 warnings to 2002, developers are unlikely to check on those 2 new issues. But if a project goes from 0 to 2 warnings, then those are going to reviewed and taken seriously.

Responsibilities

Both the author of the code and the reviewer have responsibilities during the code review process. Some of what I am going to say here might seem obvious, but it's important to state it explicitly. My goal is to make things easier for new developers who might not be familiar with the process. Avoiding the pitfalls of code reviews will make the process more enjoyable, and valuable, for everyone involved.

Reviewing bad PRs is frustrating for the reviewer, and getting bad feedback is frustrating for the author.

As the Author

As the developer requesting the review, you have a responsibility to make the process as easy as possible for the reviewer. This means making sure that your code is well-documented, well-tested, and easy to read. It also means being open to feedback and willing to make changes based on that feedback.

Some general guidelines for authors are:

- Do the Prep Work: During development you should be writing tests, updating documentation, and making sure that your code is clean and easy to read. If you are unsure about the design or your approach, then you should reach out to a team member for help before submitting the PR.

- Keep Your PR Small: Be respectful of your reviewers time and keep you changes small whenever possible. If a large change is required you should try to break it into smaller pieces that can be reviewed independently. It’s been shown that code reviews covering more than 400 lines are significantly worse at identifying issues.

- Self-Review: Before submitting your PR, you should review it yourself. This can help you catch simple bugs and make the review process faster and more efficient. If you have automated review tools available, then you should run them before submitting the PR.

- Provide Context: Make sure that your PR includes enough context for the reviewer to understand what you are trying to accomplish. This might include a description of the problem you are trying to solve, a description of the solution you have implemented, and any relevant links or documentation. If there is complicated logic in your code, then you should include an explanation of how it works.

- Expect Responsiveness: You should expect that your PR will be reviewed in a timely manner. If it isn't, then you should follow up with the reviewer to make sure that they haven't forgotten about it. Turnaround time should be hours, not days.

- Address All Feedback: When you receive feedback on your PR, you should address all of it. If you disagree with the feedback, then you should explain why. Your reviewers should feel that their feedback is being taken seriously and that they are helping to improve the codebase.

- Remember that Communication is Hard: There will always be differences of opinion when it comes to implementation choices. Always assume that the reviewer is acting in good faith and trying to help you improve your code. Avoid reading into their comments and assuming that they are attacking you personally. If something can't be cleared up quickly, arrange a meeting to discuss it in person.

As the Reviewer

When assigned a code review, you have a responsibility to provide feedback that is helpful and constructive. This means being respectful of the author's time and effort and providing feedback that is clear and actionable. It also means being open to feedback yourself and willing to learn from the author's code.

Some general guidelines for reviewers are:

- Be Courteous: Your tone should be respectful and professional. Make sure that your feedback is constructive and focused on improving the code, not on criticizing the author. Avoid using sarcasm or humor that could be misinterpreted. Always start your review by assuming that the author is competent and wants what is best for the project.

- Explain Your Reasoning: Remember that a large part of the purpose of code reviews is as an educational tool. When you suggest changes, make sure that you explain why you are suggesting them. This will help the author understand your perspective and learn from the review. It will also help them avoid making the same mistakes in the future.

- Ask for Explanations: If you don't understand something in the code, then you should ask for clarification. Don't assume that the author is wrong or that they have made a mistake. They might have a good reason for doing things the way they did. This is an opportunity for you to learn from them.

- Respond Quickly: You should respond to code review requests in a timely manner. If you can't review the code right away, then you should let the author know so that they can find someone else. I encourage teams to have a policy that code reviews should be completed no later than the end of the next business day, preferably sooner.

- Give Guidance: You need to balance suggesting a specific code change with giving the author the freedom to choose their own implementation. The reviewer's role isn't to design a better solution, but to help the author find the best solution. If you have a better idea, then you should suggest it, but you should also be open to the author's ideas.

- Avoid Bike-Shedding: Bike-shedding is the tendency to spend a disproportionate amount of time on trivial issues. You should focus on the most important aspects of the code and avoid getting bogged down in minor details. If something is a matter of personal preference, then you should let it go.

- Find an Ending: No solution will ever be perfect. At some point, you need to decide that the code is good enough and that it can be merged. When you approve a PR, you are saying that you are confident that the code is good enough to be merged. You are not saying that it is perfect. It is better to approve a PR that is 90% good than to reject it because it isn't 100% perfect.

- Question Everything: A good mindset is to assume that the author has intentionally made a mistake and is testing if you can find it. Having this mindset is especially helpful when reviewing code written by more experienced developers. There is a tendency to assume that they know what they are doing, but they can still make mistakes and will benefit from your feedback.

- Label Severity: This is a little more of a subjective preference, but I like to label my feedback with a severity level. This helps the author understand how important I think the feedback is, and lets them know if something needs to be addressed or is optional. Having the ability to label feedback as optional encourages developers to give more feedback. The exact labels will depend on your team, but I like to use the following:

- nit: minor issues without much impact. Often spelling issues or minor formatting problems.

- Optional: offers an alternative approach or suggests a minor improvement. The author can choose to ignore this feedback if they want.

- FYI: just an informational comment. The author doesn't need to do anything with this feedback, but it might be useful for them to know.

Handling Disagreements

Code reviews will inevitably lead to disagreements. The author might disagree with the reviewer's feedback, or the reviewer might disagree with the author's implementation choices. This is normal and healthy. It's a sign that the team is engaged and cares about the codebase.

When disagreements arise, it's important to handle them professionally and respectfully. Don't take them personally. A criticism of your code is not a criticism of you as a developer. Remember that everyone on the team has the same goal: to produce high-quality code that meets the project's requirements.

It can be intimidating to work with developers who have a lot more experience than you. They might be more critical of your code, or they might use terminology that you aren't familiar with. It's important to remember that they were once in your shoes. They were once new developers just starting out. They had to learn from others, and they had to make mistakes along the way.

Most senior developers are happy to help you learn and grow. They want to see you succeed, and they want to help you become a better developer, simply because it will make their lives easier as well. If you are unsure about something, then don't be afraid to ask. They will appreciate your curiosity and your willingness to learn.

To get the most out of working with senior developers, you should avoid questions like "How do I implement this?". Instead, bring a proposed solution and ask for feedback. This shows that you have put thought into the problem and that you are willing to learn from their experience.

Feedback Cycle

If a developer disagrees with your suggestion and declines to make the change, then the first thing you should do is recheck your feedback and ask yourself if it is really necessary. The author has worked more closely with the code than you have, and they might have a good reason for doing things the way they did.

Read through the author's response carefully and try to understand their perspective. Does their explanation make sense from a code health perspective? If it does, tell them that you agree with their reasoning and drop the issue. Don't skip this step. You need to be open to the idea that you might be wrong. Clearly communicating this is critical for building and maintaining trust with your team.

If after reviewing their response you still think that the change is necessary, then you should explain your reasoning in more detail. You should provide examples or references to back up your point. Be sure to directly reference and acknowledge their response. This shows that you have taken their perspective into account and that you are willing to work with them to find a solution. Giving a more detailed response will also help the author understand your perspective and make it more likely that they will agree to the change.

This cycle can repeat a few times before you reach a consensus, but don't let it drag on forever. If you can't come to an agreement after a few rounds of feedback, then you should set up a meeting to discuss the issue in person. This can help you resolve the disagreement more quickly and avoid getting bogged down in a long message chain.

Sometimes reviewers are worried that the author will become upset if the reviewer insists on some change. This is a common fear, but it's usually unfounded. As long as you've kept your comments polite and professional, the author is unlikely to become upset. Good developers welcome the opportunity to improve their code, and they appreciate feedback that helps them do that.

If a developer does become upset, it is usually because they are under a tight deadline or because they feel the tone of the feedback was rude or condescending. It is rarely the result of a reviewer insisting on quality.

Code Cleanup

There is a temptation, especially when under tight deadlines, to push back against time consuming feedback. Rushed developers will argue that the code is "good enough" and that the feedback can be address in a future PR. This is a dangerous mindset to get into. Unless the developer does the work immediately it is unlikely to ever get done. New priorities will come up, and the requested change will be forgotten. The codebase will slowly degrade.

It is generally better to insist on the cleanup now. It will take a little longer, but the codebase will be healthier in the long run. It's also easier to make changes to the code while it is fresh in your mind. If you wait until later, you will have to re-familiarize yourself with the code, which will take longer than making the change now.

Sometimes an emergency fix is necessary, and you can't afford to spend the time to make the code perfect. In those cases, you should make a note of the issue and create a follow-up ticket to address it later. Then plan to finish that work as soon as possible.

Reaching Consensus

I want to reiterate that it is critical to reach a consensus in a timely manner. If you can't come to an agreement after a few rounds of feedback, then you should set up a meeting to discuss the issue in person. Remember that clear communication is hard, and sometimes the inherent ambiguity of text-based communication can lead to misunderstandings. Talking in person can help you resolve the disagreement more quickly and clear up any bruised egos or hurt feelings.

If things can't be resolved in person, then you may need to escalate the issue to a team lead or manager. This should be a last resort, and you should only do it if you feel that the disagreement is negatively impacting the team or the project. Remember that the goal of the code review process is to improve the codebase, not to win arguments. If you can't come to an agreement, then you should be willing to compromise.

Regardless of any disagreements, don't let a PR sit in limbo. Find a way to move the process forward.

Conclusion

Providing quality feedback during a code review is a skill that takes time to develop. It requires a combination of technical knowledge, communication skills, and empathy. It's important to remember that the goal of a code review is to improve the overall quality of the codebase, not to criticize the author or show off your own knowledge.

When seeking feedback on your own code, it's important to be open to criticism and willing to make changes based on that feedback. Remember that everyone on the team has the same goal: to produce high-quality code that meets the project's requirements. By working together and supporting each other, you can create a codebase that is clean, maintainable, and easy to work with.